In a recent conversation at his studio in Newport, Richard Saul Wurman reminded me of the terrific Japanese movie classic Rashômon and pointed out an interesting take-away for the design process: In any situation, the different stakeholders can and will have diverse, diverging and even contradicting viewpoints on the very situation you are trying to address. We were having a conversation about healthcare and the circumstance of having to mediate between viewpoints of caretakers, caregivers, supporting family members, etc.

Exploring and shedding light on this multiplicity of viewpoints is critical for a designer in order to get to the underlying issues, challenges and opportunities. Because these real issues at hand are the only ones through which to bring about real change.

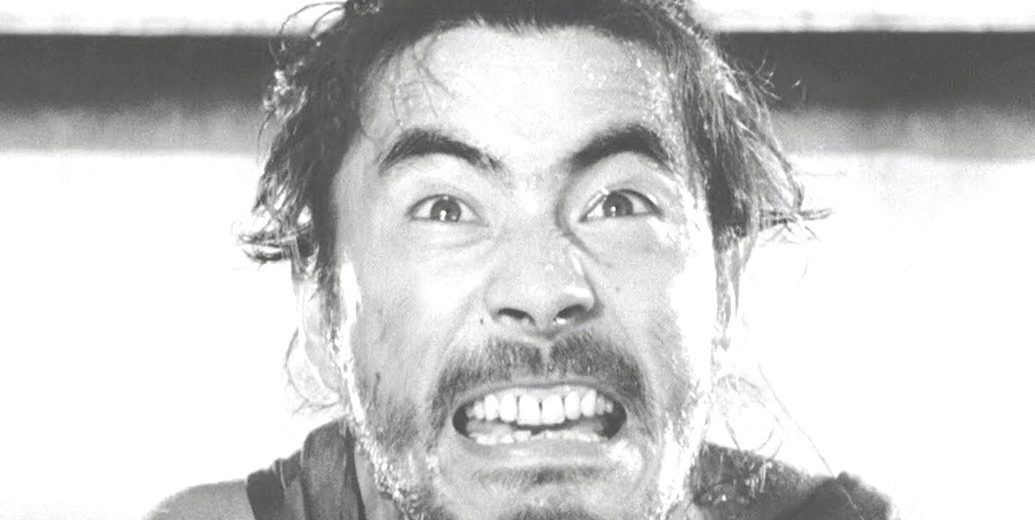

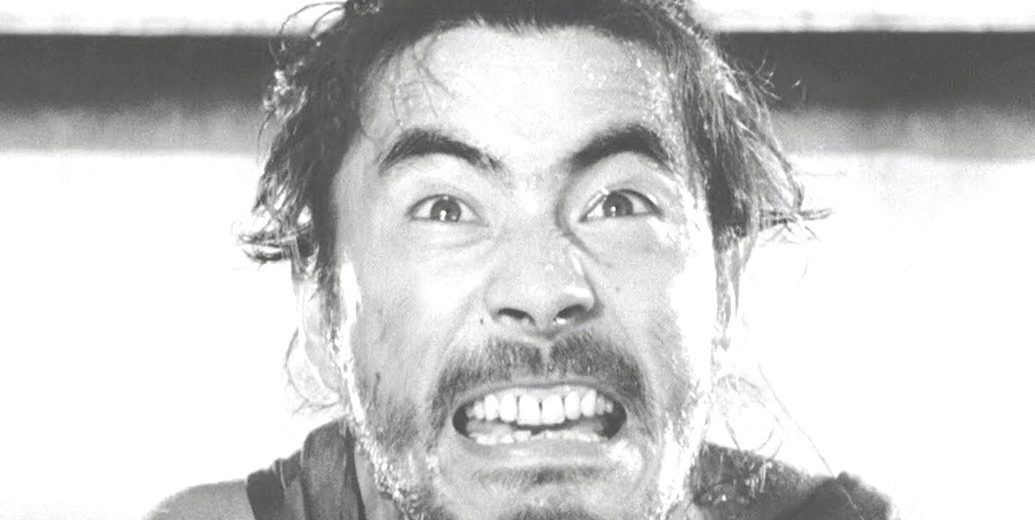

In Rashômon (directed in 1950 by Akira Kurosawa with cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa), the one dramatic story that leads to the death of a Samurai is recounted by the four characters present at the scene: the bandit Tajōmaru, the Samurai’s wife, the Samurai, and the woodcutter who observed the events unnoticed. Each of the characters tells a very different story of what happened and why. The agents differ, the culprits are inverted, the motives are varied. We walk away with not knowing what ‘actually’ happened, with a longing for clarity, for truth. However, we do get to know the characters through their individual narration.

When designing for healthcare, we are faced with multiple viewpoints: of caretakers, caregivers, family supporters, and others. When designing for services in general this holds true. There always exist multiple viewpoints in any situation and these viewpoints can be anything from converging to outright contradictory and diverging. They can be self-serving, serving individual interests whether these are external or internal, conscious or unconscious. They can point away from the core issues that contain seeds of resolution.

Exploring and shedding light on this multiplicity of viewpoints is critical for a designer in order to get to the underlying issues, challenges and opportunities. Because these real issues at hand are the only ones through which to bring about real change.

Rashômon ends with a scene of hope. At the massive city gates of Kyoto, from which the movie takes its name, and after narrating the disturbing incident to a priest, the woodcutter makes a gesture of selflessness. He makes a sacrifice by taking on an orphan newborn they discover at the gate and through this reveals an instance of truth. Truth that is what we were longing for throughout the story of the murder. Truth that points to a possible resolve.

In a recent conversation at his studio in Newport, Richard Saul Wurman reminded me of the terrific Japanese movie classic Rashômon and pointed out an interesting take-away for the design process: In any situation, the different stakeholders can and will have diverse, diverging and even contradicting viewpoints on the very situation you are trying to address. We were having a conversation about healthcare and the circumstance of having to mediate between viewpoints of caretakers, caregivers, supporting family members, etc.

In Rashômon (directed in 1950 by Akira Kurosawa with cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa), the one dramatic story that leads to the death of a Samurai is recounted by the four characters present at the scene: the bandit Tajōmaru, the Samurai’s wife, the Samurai, and the woodcutter who observed the events unnoticed. Each of the characters tells a very different story of what happened and why. The agents differ, the culprits are inverted, the motives are varied. We walk away with not knowing what ‘actually’ happened, with a longing for clarity, for truth. However, we do get to know the characters through their individual narration.

When designing for healthcare, we are faced with multiple viewpoints: of caretakers, caregivers, family supporters, and others. When designing for services in general this holds true. There always exist multiple viewpoints in any situation and these viewpoints can be anything from converging to outright contradictory and diverging. They can be self-serving, serving individual interests whether these are external or internal, conscious or unconscious. They can point away from the core issues that contain seeds of resolution.

Exploring and shedding light on this multiplicity of viewpoints is critical for a designer in order to get to the underlying issues, challenges and opportunities. Because these real issues at hand are the only ones through which to bring about real change.

Rashômon ends with a scene of hope. At the massive city gates of Kyoto, from which the movie takes its name, and after narrating the disturbing incident to a priest, the woodcutter makes a gesture of selflessness. He makes a sacrifice by taking on an orphan newborn they discover at the gate and through this reveals an instance of truth. Truth that is what we were longing for throughout the story of the murder. Truth that points to a possible resolve.